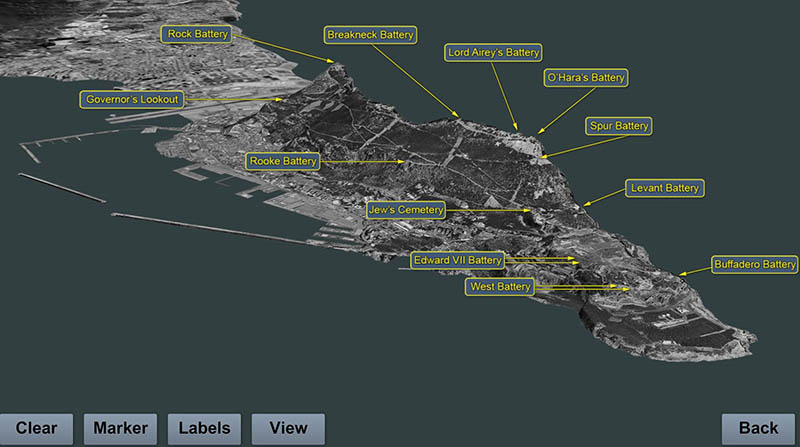

As seen at O'Haras Battery in the Upper rock Nature Reserve - Gibraltar

Game

This game is based on the British BL 9.2” Guns which were used in the coastal defence of Gibraltar during WW1 and WW2.

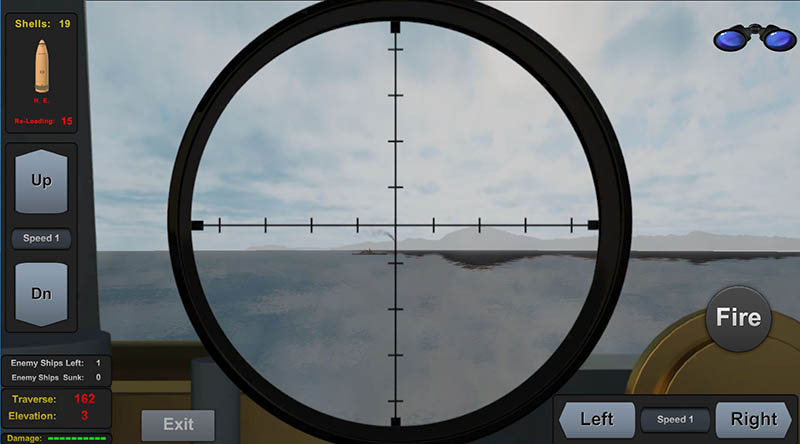

You will have to defend Gibraltar from the attacking enemy ships using the BL 9.2 Gun!

You win when you sink all the enemy ships, you lose if the enemy destroys your gun.

The damage to your gun is repaired at the end of every level.

Loading and firing the gun has been kept as accurate as possible while taking into account game playability.

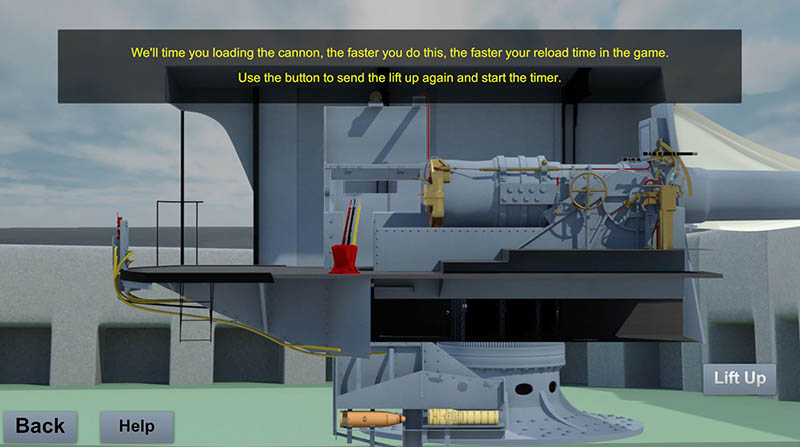

When you start the game you will first have to load the cannon, the time you take to get the gun Ready To Fire will be recorded and used as the minimum loading time between shells.

You can select from different types of ordnance which unlock and become available as you progress through the game levels.

You can do this by tapping on the ordnance icon available at the cannon sights window.

Once you select an ordnance type it becomes the default unless you change by going through the loading sequence.

You can start firing the gun at the enemy ships after it has been loaded.

Click here to downwload a free copy of this game (no adverts or spamware). [Self extracting winzip executable file]History

The BL 9.2 inch guns Mk IX and Mk X were British breech loading 9.2 inch guns of 46.7 calibre, in service from 1899 to the 1950s as naval and coast defence guns. They had possibly the longest, most varied and successful service history of any British heavy ordnance.

These guns succeeded the 9.2 inch Mk VIII and increased the bore length from 40 to 46.7 calibres, increasing the muzzle velocity from 2,347 feet per second (715 m/s) to 2,643 feet per second (806 m/s).

The Mk IX was designed as a coast defence gun, with a three-motion breech. Only fourteen were built and the Mk X, introduced in 1900, incorporated a single-motion breech and changed rifling, succeeded them. As coastal artillery, the Mk X remained in service in Britain until 1956, and in Portugal until 1998. 284 of the Mark X version were built by Vickers, of which 28 examples are known to survive today, all except one fitted on barbette mounts. One in Cape Town is on a disappearing mount.

The 9.2 inch Mk XI gun introduced in 1908 increased the bore length to 50 calibres in an attempt to increase the velocity still further, but proved unsuccessful in service and was phased out by 1920. The Mk X was hence the final Mark of 9.2 inch guns in British Commonwealth service.

These were 'counter-bombardment' guns designed to defeat ships up to heavy cruisers armed with 8-inch guns. They were deployed in the fixed defences of major defended ports throughout the British Empire until the 1950s.

Their role was to defeat enemy ships attacking the ships in a port, including warships, alongside or at anchor in the port. However, where guns covered narrows, such as the Dover Straits, the Straits of Gibraltar, or the Narrows of Bermuda, they also had a wider role of engaging enemy ships passing through the straits. Normally deployed in batteries of two or three guns, a few major ports had several batteries positioned miles apart.

There were several marks of mountings and a battery had extensive underground facilities in addition to the guns visible in their individual gun-pits. Together with the 6-inch Mk VII, they provided the main heavy gun defence of the United Kingdom in World War I. 3 Mk IX and 53 Mk X guns were in place as of April 1918.

The Mounting Barbette Mark V (the original mounting with Mark IX and X guns) gave a maximum elevation of 15 degrees, and maximum range of 21,000 yards. This and some modified to Mark VI (30 degrees and 29,500 yards) were manually powered, the projectile and propelling charge were manually hoisted to loading level, the projectile manually loaded and rammed, and traverse and elevation were by handwheels. There was an elevated platform around the breech area for the gun detachment commander (No 1) and some detachment members, and a gun shield to the front. The ordnance and mounting together weighed some 125 tons, they were well balanced and the handwheels needed very little effort to move the gun.

However, the Mark VII mounting appeared in the 1930s and in 1939 a simplified version, Mark IX. Both were hydraulically powered and the platform was enclosed in a roofed gun house with three sides (and rear with Mark IX). The hydraulics meant that both projectile and propelling charge could be hoisted in a single load. With Mark VII and IX the maximum elevation was increased to 35 degrees to give a maximum range of 36,700 yards.

Each gun mounting was installed on a central cast-steel pedestal in an open concrete gunpit 35 feet in diameter and 11 feet deep. The gun and mounting weighed 125 tons. A very narrow gauge rail track was embedded around the gunpit floor. A trolley was manhandled around the track between the two ammunition lifts (one for projectiles, one for propelling charges) and the rear of the gun (this position varied depending on where the gun was pointed).

Below the gun pit were the separate ammunition bunkers for projectiles and shells with direct access to the ammunition lifts. These bunkers had an access road leading to them for ammunition re-supply. The guns presented only a very small target above ground level, guns and gunpits were camouflaged.

Increasing ranges led to new centralised control arrangements. Fortress observation posts, equipped with rangefinders and directors were sited 4000 – 10,000 yards apart to give observation of all the sea area within range. They reported enemy ship bearings and distances to the ‘fortress plotting

The observers also reported fall of shot relative to the targets, the FPC used an encoder to convert these into a clock code, which the battery converted to its left/right, add/drop corrections. Various types of radars integrated into the fire command soon became widespread in WW2 and enabled effective night engagements.

[From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia]